"Only librarians like to search, Everyone else likes to find."

Roy Tennant

(Roy Tennant is an internationally recognized thought leader in library technology. He is the owner of the Web4Lib and XML4Lib electronic discussions, and the creator and editor of Current Cites, a current awareness newsletter published every month since 1990. Roy wrote a monthly column on digital libraries for Library Journal for a decade and has written numerous articles in other professional journals. In 2003, he received the American Library Association's LITA/Library Hi Tech Award for Excellence in Communication for Continuing Education.)

This quote by Mr. Roy Tennant initially appeared in an article published in the Library Journal in October 2001 entitled Digital Libraries - Cross-Database Search: One-Stop Shopping. In the article, he talks about searching in multiple databases through a single interface. The first paragraph contains his iconic quote:

In the second paragraph he says:

Tennant lists several services that would allow librarians and users to gather search results more easily from a variety of resources. He concludes by saying that implementing such systems will pose challenges, but that librarians realize the importance of trying to work with them. Tennant actually encourages librarians to make searches easier for everyone. Most of the times the library patrons just want a quick and easy answer while the librarians try to show them searching in the databases subscribed by the library. Librarians understand the difficulties of searching the databases as the databases may follow different standards for the organization of information and indexing. So, the librarians feel an obligation to explain the patrons about various databases so that they can find what they need.

You know you want it. Or you know someone who does. One search box and a button to search a variety of sources, with results collated for easy review. Go ahead, give in—after all, isn’t it true that only librarians like to search? Everyone else likes to find.

In the second paragraph he says:

In the past, we might argue that such a wide-ranging search service was too difficult or impossible to build. It remains difficult, certainly, but such a service can no longer be called impossible, as these examples show.

Tennant lists several services that would allow librarians and users to gather search results more easily from a variety of resources. He concludes by saying that implementing such systems will pose challenges, but that librarians realize the importance of trying to work with them. Tennant actually encourages librarians to make searches easier for everyone. Most of the times the library patrons just want a quick and easy answer while the librarians try to show them searching in the databases subscribed by the library. Librarians understand the difficulties of searching the databases as the databases may follow different standards for the organization of information and indexing. So, the librarians feel an obligation to explain the patrons about various databases so that they can find what they need.

The impact of this iconic quote of Roy Tennant is clearly visible on modern information retrieval systems. Modern catalog interfaces just keep "One search box and a button to search a variety of sources, with results collated for easy review" as was suggested by Roy Tennant.

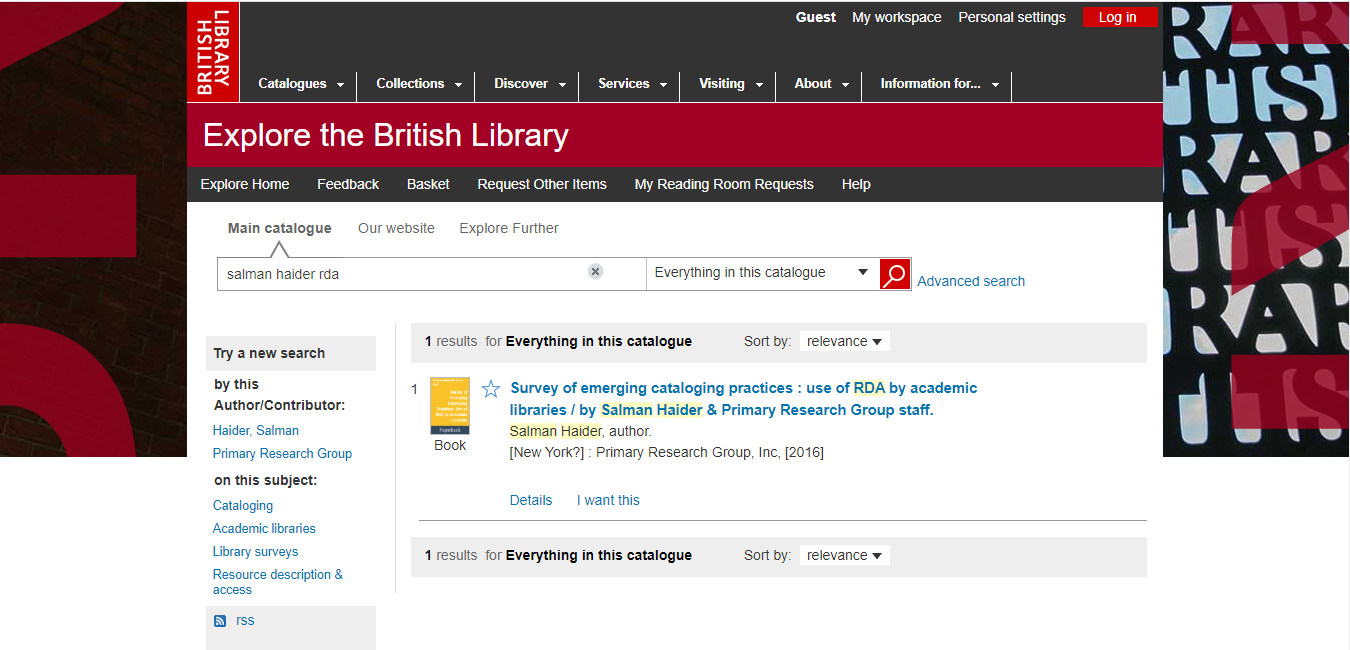

Let us see this with the interfaces of the catalogs of the two biggest libraries of the world, viz. the Library of Congress and the British Library. The online public access catalog of both these libraries has one search boxes and a button to search a variety of sources of the respective library. Now assume there is some researcher of library cataloging who is searching a book on RDA authored by Salman Haider. The researcher will go directly to the online catalog of the library, as shown in Picture 1 and Picture 2. There he/she will type simple keywords "Salman Haider RDA" and hit the search button, which will give him/her the search results collated as a list for easy review.

Picture 1.1: Library of Congress Catalog (https://catalog.loc.gov/)

Picture 1.2: Library of Congress Catalog - search results

Picture 2.1: British Library Catalogue (http://explore.bl.uk/)

Picture 2.2: British Library Catalogue - search results

The complete article by Roy Tennant published in the Library Journal is given below:

Cross-Database Search: One-Stop Shopping

10/15/2001

You know you want it. Or you know someone who does. One search box and a button to search a variety of sources, with results collated for easy review. Go ahead, give in--after all, isn't it true that only librarians like to search? Everyone else likes to find.

Why should we make our users hunt down the best resource for a given information need and learn how to use its particular options for searching? Why not provide them with a simple way to get started? In the past, we might argue that such a wide-ranging search service was too difficult or impossible to build. It remains difficult, certainly, but such a service can no longer be called impossible, as these examples show.

Cross-database search services

Some early adopters of this type of technology use commercial applications, while others have built their systems from scratch. Unfortunately, because most search commercial databases, the curious are often locked out. However, in a message to the Web4Lib electronic discussion ("Cross-Database Search Tools Summary"), I listed some staff contacts for some of these services. Also, some are publicly searchable. Searchlight. The California Digital Library (CDL) has offered its Searchlight tool since January 2000. Based on the Database Advisor service of the University of California (UC)-San Diego, Searchlight offers one-stop searching of abstracting and indexing databases, library catalogs, and web sites, as well as other types of resources. After selecting which "flavor" of Searchlight they wish to search (either "Sciences and Engineering" or "Social Sciences and Humanities"), users type in the search. An intermediary screen describes what is happening and also counts down the minute that it will take by default before results are returned (this can be adjusted by the user). The user's search words are sent to a wide variety of databases (well over 100), with the results organized by resource type (books, journal indexes, electronic journals, e-texts and documents, reference resources, and web directories). The number of hits is noted beside each resource, and clicking on that number will automatically take users to the results in that particular database when possible. Alternatively, they can click on a link to go to the resource and search it directly. Anyone can try it out, but those not part of the UC community won't see results for licensed databases. The CDL is planning to gather user feedback this fall on how it works for its own needs and then consider where to take the service. Possible future directions may include subject-focused cross-database search tools (for example, one-stop searching of all the best resources in a particular discipline), or a tool optimized for the needs of undergraduates to find "a few good things" on a topic. NLM Gateway. This cross-database search operates in a variety of databases from the National Library of Medicine (NLM). A web page describing the service states, "One target audience for the Gateway is the Internet user who is new to NLM's online resources and does not know what information is available there or how best to search for it." Flashpoint. The Research Library of the Los Alamos National Laboratory wrote an in-house Perl program to search a set of databases simultaneously. In the article "Flashpoint @ LANL.gov: A Simple Smart Search Interface," the authors describe how their system underwent several design iterations in response to user feedback, testing, and analysis of failed searches. It presently searches nine bibliographic databases and one full-text database. King County Library Search. The King County Library System in Washington State uses the commercial product WebFeat to offer one-stop searching of its library catalog, web site, and ProQuest databases. The system was released in November 2000 for user testing, so not all the databases planned to be included are yet covered. Users are limited to library cardholders. Multi-SEARCH. The University of Arizona Library uses OCLC's SiteSearch software to search multiple databases. SiteSearch uses the Z39.50 protocol to search databases that are compliant with that standard--in this case, three state catalogs and the OCLC FirstSearch databases.

Some early adopters of this type of technology use commercial applications, while others have built their systems from scratch. Unfortunately, because most search commercial databases, the curious are often locked out. However, in a message to the Web4Lib electronic discussion ("Cross-Database Search Tools Summary"), I listed some staff contacts for some of these services. Also, some are publicly searchable. Searchlight. The California Digital Library (CDL) has offered its Searchlight tool since January 2000. Based on the Database Advisor service of the University of California (UC)-San Diego, Searchlight offers one-stop searching of abstracting and indexing databases, library catalogs, and web sites, as well as other types of resources. After selecting which "flavor" of Searchlight they wish to search (either "Sciences and Engineering" or "Social Sciences and Humanities"), users type in the search. An intermediary screen describes what is happening and also counts down the minute that it will take by default before results are returned (this can be adjusted by the user). The user's search words are sent to a wide variety of databases (well over 100), with the results organized by resource type (books, journal indexes, electronic journals, e-texts and documents, reference resources, and web directories). The number of hits is noted beside each resource, and clicking on that number will automatically take users to the results in that particular database when possible. Alternatively, they can click on a link to go to the resource and search it directly. Anyone can try it out, but those not part of the UC community won't see results for licensed databases. The CDL is planning to gather user feedback this fall on how it works for its own needs and then consider where to take the service. Possible future directions may include subject-focused cross-database search tools (for example, one-stop searching of all the best resources in a particular discipline), or a tool optimized for the needs of undergraduates to find "a few good things" on a topic. NLM Gateway. This cross-database search operates in a variety of databases from the National Library of Medicine (NLM). A web page describing the service states, "One target audience for the Gateway is the Internet user who is new to NLM's online resources and does not know what information is available there or how best to search for it." Flashpoint. The Research Library of the Los Alamos National Laboratory wrote an in-house Perl program to search a set of databases simultaneously. In the article "Flashpoint @ LANL.gov: A Simple Smart Search Interface," the authors describe how their system underwent several design iterations in response to user feedback, testing, and analysis of failed searches. It presently searches nine bibliographic databases and one full-text database. King County Library Search. The King County Library System in Washington State uses the commercial product WebFeat to offer one-stop searching of its library catalog, web site, and ProQuest databases. The system was released in November 2000 for user testing, so not all the databases planned to be included are yet covered. Users are limited to library cardholders. Multi-SEARCH. The University of Arizona Library uses OCLC's SiteSearch software to search multiple databases. SiteSearch uses the Z39.50 protocol to search databases that are compliant with that standard--in this case, three state catalogs and the OCLC FirstSearch databases.

Software for cross-database searching

Several sites use the WebFeat product to search multiple databases. Other products that offer similar capabilities include Fretwell-Downing's Zportal, MetaLib from Ex Libris, Copernic Aggregator, Endeavor ENCompass, and OCLC's SiteSearch. Several other site developers have written their own software but then must maintain it as resources (search targets) change. More libraries than those noted above are developing their own cross-database search services, including OhioLink and the National University of Mexico (UNAM). It's clear that there is a widely perceived need for one-stop searching of bibliographic databases, though it is also too early to have much data yet on what features are essential. One key challenge for software of this type is how to package up the search and process the results. Unless the database supports the Z39.50 search protocol, it can be daunting to deal with the particular needs of a proprietary database. Even if sending the search is straightforward, the results may emerge via a somewhat primitive technique called "screen scraping." Screen scraping is the process of collecting needed information by clues such as the location of the information on the screen. The problem is that the slightest change in screen displays can break your process. Some applications are limited to Z39.50 databases, while others (such as Searchlight) encompass other databases as well. In general, the more databases a search service covers the more challenges it will face. Some early experience indicates that simply broadcasting the search and getting back results from separate databases is a start but not what most users really want or expect. Most users likely want such features as deduping (dropping duplicate records from different databases), merging and ranking (instead of keeping the results separated by the source), and methods for trimming down or sorting the results set. Unfortunately, most of these features are likely to be somewhat difficult to achieve and probably extremely difficult to achieve with much accuracy. But increasingly, librarians serving user groups from the general public to academic researchers are realizing that it is a goal well worth pursuing.

Several sites use the WebFeat product to search multiple databases. Other products that offer similar capabilities include Fretwell-Downing's Zportal, MetaLib from Ex Libris, Copernic Aggregator, Endeavor ENCompass, and OCLC's SiteSearch. Several other site developers have written their own software but then must maintain it as resources (search targets) change. More libraries than those noted above are developing their own cross-database search services, including OhioLink and the National University of Mexico (UNAM). It's clear that there is a widely perceived need for one-stop searching of bibliographic databases, though it is also too early to have much data yet on what features are essential. One key challenge for software of this type is how to package up the search and process the results. Unless the database supports the Z39.50 search protocol, it can be daunting to deal with the particular needs of a proprietary database. Even if sending the search is straightforward, the results may emerge via a somewhat primitive technique called "screen scraping." Screen scraping is the process of collecting needed information by clues such as the location of the information on the screen. The problem is that the slightest change in screen displays can break your process. Some applications are limited to Z39.50 databases, while others (such as Searchlight) encompass other databases as well. In general, the more databases a search service covers the more challenges it will face. Some early experience indicates that simply broadcasting the search and getting back results from separate databases is a start but not what most users really want or expect. Most users likely want such features as deduping (dropping duplicate records from different databases), merging and ranking (instead of keeping the results separated by the source), and methods for trimming down or sorting the results set. Unfortunately, most of these features are likely to be somewhat difficult to achieve and probably extremely difficult to achieve with much accuracy. But increasingly, librarians serving user groups from the general public to academic researchers are realizing that it is a goal well worth pursuing.

SEE ALSO

- Roy Tennant

- Best Quotes About Libraries Librarians and Library and Information Science: Most Beautiful Quotations About Libraries, Librarians, Cataloging, Classification, Catalogers, and Library and Information Science. Famous quotes describing why libraries and cataloging important and librarians and catalogers indispensable. Includes inspirational and motivational quotes from famous personalities for personality development, personal development, self-improvement, and achieving greater success in personal and professional life.

- Library and Information Science Encyclopedia - An Online Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences. It provides articles on librarianship studies, library science, information science, information technology, information and knowledge organization, and management. The encyclopaedia includes articles on everything from traditional library terms to a vocabulary of modern avenues in information science and technology. Encyclopedia articles will include anything and everything required for an advanced study and reference on the Library and Information Science (LIS) topics, including biographies of famous librarians.

REFERENCES

- Roy Tennant, "Cross-Database Search: One-Stop Shopping," Library Journal, https://www.libraryjournal.com/?detailStory=cross-database-search-one-stop-shopping (accessed May 8, 2020).

- Roy Tennant, "Library Journal "Digital Libraries" Columns 1997-2007, Roy Tennant," http://roytennant.com/column/?fetch=data/69.xml (accessed May 7, 2020).

- Thus Spoke Pragmatic Librarian, "Do librarians really like to search?" https://pragmaticlibrarian.wordpress.com/2007/01/10/do-librarians-really-like-to-search/ (accessed May 7, 2020).

CITATION INFORMATION

Article Title

- Only librarians like to search, Everyone else likes to find

Article Author

- Salman Haider

Website Name

- Librarianship Studies & Information Technology

URL

- https://www.librarianshipstudies.com/2020/05/only-librarians-like-to-search-everyone-else-likes-to-find.html

Last Updated

- Last Updated: 2020-05-08

Original Published Date

- Written: 2020-05-07

FEEDBACK

- Help us improve this article! Contact us with your feedback. We would be happy to include important and interesting comments in this article. You can use the comments section below, or reach us on social media.

Some feedback and comments received on this article are given below:

- Martha Rice Sanders (Senior Systems Librarian at Innovative Interfaces, United States) - and it is catalogers who facility 'finding'.

- Stephen T. - Early But personally, I vastly prefer finding over searching. That's what cataloging is all about, right? But having really good searching skills makes it a lot easier to find stuff quickly.

- Mario Rups - In an academic library, cataloguing is all about the searching, too -- you need to have a basic understanding of what the book is about if it's not a subject with which you're familiar, and then of course the searching for the nearest usable subject headings to apply, but that's another kind of search.

- Joy Krause Shoop - I actually enjoyed your thoughtful dissection of the use of Tennant’s quotation, so I’m not at all trying to start anything. My comment simply meant that I see the meaning of his quotation in the context that he presented it. And so I’m not going to sweat taking it out of context.

- James Weinheimer (Information Specialist, Rome, Italy) - My ideas on this have gone back and forth. I will state unequivocally that (most) people do not enjoy searching a catalog and they never have. (I am one of the very few that does enjoy it). Spending time working with the public where I heard many variations of the question "Where are your books on ...?" and my invariable answer (correct) "The books can be everywhere. You need to look in the catalog. Let me help you" and the pained looks on their faces at my reply, convinced me that what people actually love is to search the *collection* (that is, browse the materials) but they do not like to use the catalog. I did NOT like learning this lesson. I think my experience has been shared with other librarians from a long time back, probably centuries old if not millennia. Why is this? I think there are many reasons, and there may be all kinds of solutions, but this is not the place for such indepth thought.

- Jay Towne Smith (San Francisco, United States) - Regarding Salman Haider's post on Roy Tennant's 2001 article, "Only librarians like to search, everyone else likes to find."I do sometimes find Roy Tennant's pronouncements tedious, and this one falls into that category. Librarians, whether Mr. Tennant likes to acknowledge it or not, have an obligation to try to verify whether library patrons/clients/whoever are finding what they need, not just "something," and to point out what they might have missed among all the resources out there. I do understand that many people would prefer not to have a lengthy interaction even if the librarian is primed to "teach" searching. A single library "search box" does indeed increase the likelihood of finding *something* but it may not be relevant or right or even include critical search terms, and rarely does the search box explain how the results were arrived at. I particularly dislike when it returns "something" as a sort of consolation prize though precise terms were given. I'm not talking about search engines that suggest or try alternate spellings since people often mis-type. That is all to the good. The "answer" when the right something actually *is not* found should be, "We don't have precisely what you asked for, but you may be interested in the following." This is essentially the Amazon "some customers instead selected X" result.